One word has exploded a world of new-to-me authors and books: podcasts.

That’s how I found out about Lidia Yuknavitch, author of two short story collections, the ground-quaking body-centric memoir, The Chronology of Water, a novel about Freud’s famous first patient, Dora: A Headcase, and her latest fiction, a heart shattering and language loving novel, The Small Backs of Children.

I don’t often review books on this blog (hey, maybe I will) but after reading my first Lidia I felt a shift, the seismic kind. So often, reading removes me from my body. You probably know what I mean, when immersed in a riveting story, you lose your physical self and float away in a time-space oblivion. But this time the opposite occurred. Reading The Small Backs of Children I was as fully aware of my body’s responses to her words as I was to my brain’s.

The book was intense and when I finished I felt shaken and stirred (sorry, but there’s a lot of drinking as well as violence and beauty). Shortly after, I began writing my first short story in two years. I know her influence left an impression on the choices I made in regards to language and the body.

Are you curious yet? My review is below, and shortly, I will be sending out a long-awaited newsletter with an exhaustive – but thrilling (!) podcast round-up. If you’re not a podcast convert yet, you may be by the end. Please consider signing up (CLICK HERE!) for my newsletter if you haven’t already. Believe me when I say you won’t be inundated. Maybe monthly, if the stars and planets align.

Now, finally…

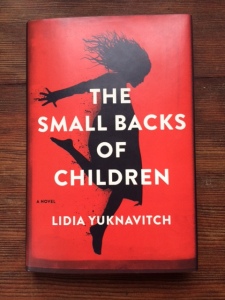

The Small Backs of Children by Lidia Yuknavitch

This is a book about the body. Women and children’s bodies, and the violence inflicted on them during times of war and peace.

Yuknavitch begins in the mind of an unnamed girl, in an unnamed Eastern European country, as she recalls the obliteration of her family home – and entire family – while walking in the snowy woods a year later.

In many ways, the girl is the focal point of the story, the sun which all the other characters orbit. None of these characters have names. They are a band of artists identified only by their work: writer, photographer, painter, poet, playwright, and filmmaker. When the writer of the group falls ill, unable to come back from the oceanic grief of losing her stillborn child, her friends rally to help.

The intersection of the girl and these artists make up the plot, but the idea of “plot” is used loosely as this book defies conventions on every level. Early on, Yuknavitch plays with the translucence of fiction and memoir by including biographical information in the story. The Writer even says, “Every self is a novel in progress. Every novel is a lie that hides the self.”

Is the Writer a thinly veiled Yuknavitch, an echo of her lived experience? Is she playing with us in this passage? How much of the book is based on fact and how much is fiction?

But this wonder is soon set aside. There are more pressing issues at hand. Sweeping philosophical questions with no definitive answers arise, including – how is motherhood defined, can art save lives, and what responsibility does an artist have to her subjects? All this is juxtaposed alongside explicit sequences of torture and sex (sometimes consensually, sometimes not).

Yuknavitch writes with ferocity, as if she’s daring the reader to look away. As she explains in an interview with The Rumpus, the goal of this book isn’t to entertain or comfort; the point is to agitate.

Agitation may be an understatement for some readers. Despite being deeply invested in the book, even I had some moments of discomfort, but I kept reading. Maybe it’s like a highway car accident, how other drivers slow down to look. Once viewed there is no un-seeing the carnage, and that is the point of this book. Yuknavitch wants readers to be changed, and I imagine many will.

One thing that struck me about this book was how acutely aware I was of my own body while reading it. Usually when reading fiction, I lose myself. I become unaware of the passage of time and my own physicality. But instead of disappearing, my body was complicit, cringing and humming along with the characters’ experiences.

This novel is not for the fainthearted. Trigger warnings abound. There is blood, lots of it, but as the narrator says toward the end, “You wish I would stop speaking about all this blood, but I’m afraid it’s the point.”

Yes, it is, because this is a novel about the body, about pain inflicted, but also pleasures amassed. Despite all the horror, Yuknavitch celebrates the resilience and strength of bodies. How sometimes, with luck, the heart will continue to pump despite the scars, despite the weight of grief we all carry.

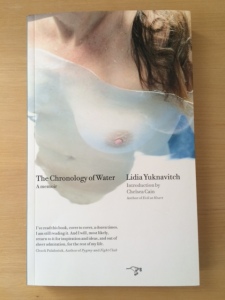

(Highly) Suggested pairing: Yuknavitch’s memoir, The Chronology of Water.

What books and/or authors have you stumbled upon that have changed your life/rocked your literary world? Please share in comments. I’d love to know.

PLEASE write more book reviews. This is wonderful. I’m ordering this book today!

LikeLike

This comment just made my whole day. Thank you Lindsey! xoxo

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

I’d love to sign up for the newsletter. I’m a HUGE podcast devotee so we can compare lists. I didn’t see the sign up though?

LikeLike

Thank you Nina! My site doesn’t allow hyperlinks to show up, so I just made it more obvious in the blog post, but also if you scroll down, there’s a link on the right sidebar.

LikeLike

Lidia Yuknavitch is incredible. I haven’t read Smalls Backs yet, but I can’t recommend the memoir enough. It’s so gorgeous, it hurts. I second more book reviews here!

LikeLike

Oh yes, I’m loving Chronology. I completely lose track of time while reading it, so riveting and painful. I think it’s interesting to read both, one informs the other.

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just subscribed because I want more information and I loved this post. You didn’t send it out yet, did you?!

LikeLike

Not yet! Thank you 🙂 And it’s so funny because I’m reading and loving your latest post 🙂 That tantrum article was incredible and moving.

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

Powerful review, Dana. Agitated is a great word – I felt quite restless as I read her prose. I will definitely check out her memoir. Thank you and I love your book review style. Please do more!

LikeLike

Thank you, Rudri, for your kind words! Yes, restless is a great descriptor. Her memoir is currently blowing me away.

LikeLike